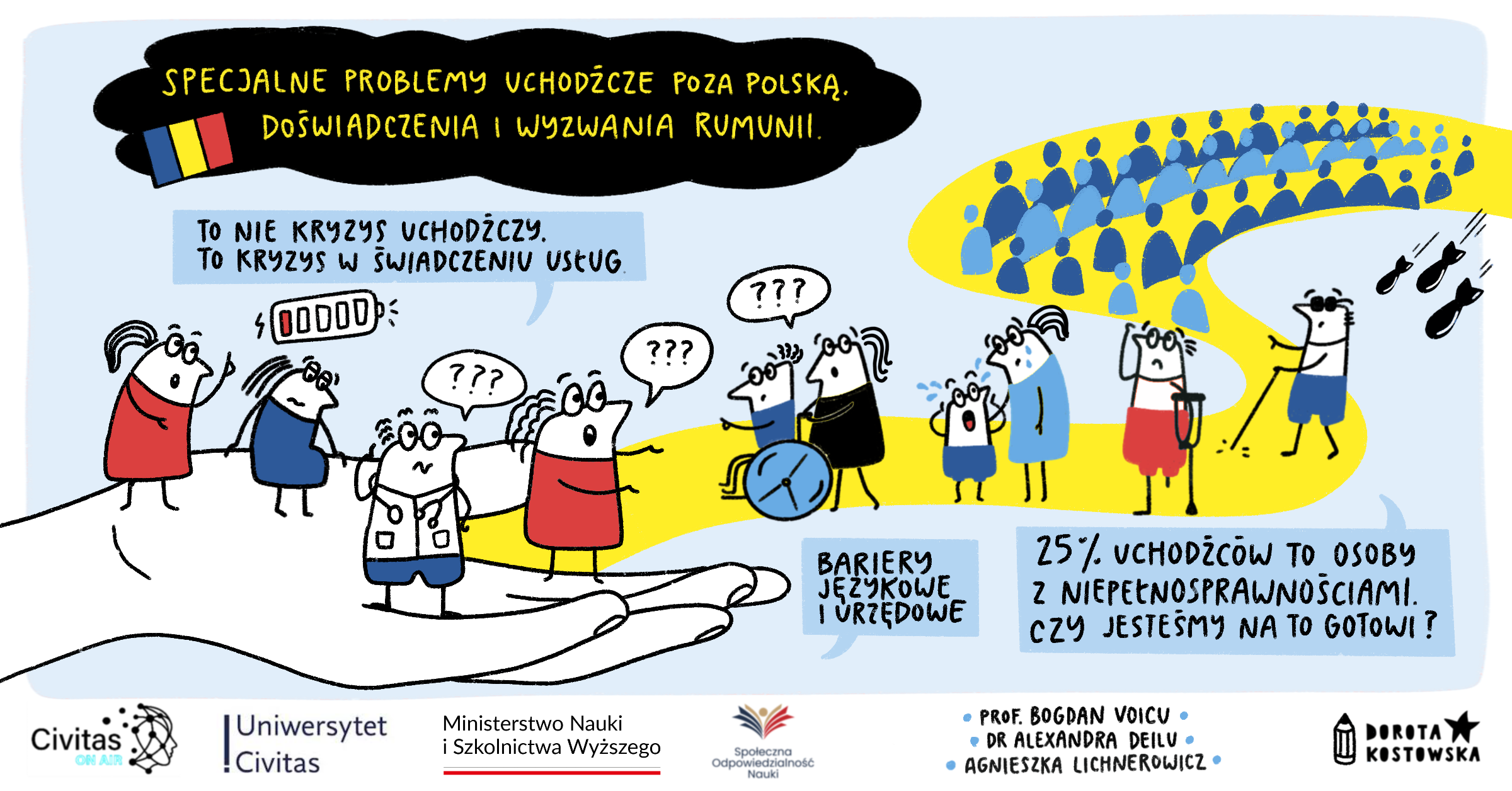

Specjalne problemy uchodźcze poza Polską. Doświadczenia i wyzwania Rumunii (podcast w języku angielskim) | Społeczeństwo Łatwopalne #10

W 2022 roku miliony Ukrainek i Ukraińców uciekły przed wojną do Polski i Rumunii. Wśród nich znalazły się także osoby z niepełnosprawnościami – zupełnie nowa grupa uchodźców, na którą oba państwa nie były przygotowane.

Jak reagowały społeczeństwa? Jaką rolę odegrały organizacje pozarządowe i lokalne wspólnoty? Czego nauczyliśmy się na przyszłość?

W 10. odcinku podcastu „Społeczeństwo Łatwopalne” dziennikarka Agnieszka Lichnerowicz rozmawia z prof. Bogdanem Voicu i dr Alexandrą Deilu z Research Institute for Quality of Life w Rumuńskiej Akademii Nauk o wspólnych doświadczeniach Polski i Rumunii, wnioskach z projektu “The Capacity of Polish and Romanian Stakeholders to provide support to Ukrainian refugees with disabilities” oraz o powstałym na jego podstawie praktycznym narzędziowniku (toolkicie) dla organizacji pomocowych.

🎧 Podcast w języku angielskim.

______________

Projekt „Podcasty i filmy popularyzujące nauki socjologiczne – rozwój kanału Civitas on Air” został dofinansowany ze środków budżetu państwa przyznanych przez Ministerstwo Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego w ramach programu „Społeczna odpowiedzialność nauki II – Popularyzacja nauki”

Rysunki wykonała Dorota Kostowska.

TRANSKRYPCJA ODCINKA

tytuł: Specjalne problemy uchodźcze poza Polską. Doświadczenia i wyzwania Rumunii

Intro: Słuchasz podcastu Civitas On Air. Civitas On Air. Nauka w zasięgu ręki. Zaangażowanie, neutralność, wrogość. Jakie postawy i zachowania cechują Polki i Polaków wobec wojny w Ukrainie i wobec uchodźców wojennych, którzy dotarli do Polski? W podcaście „Społeczeństwo łatwopalne” badaczki i badacze z Instytutu Socjologii Uniwersytetu Civitas przyjrzą się temu, jak polskie społeczeństwo odnajduje się w obliczu wojny, o której mówimy „To jest nasza wojna”, a także jak radzimy sobie ze stałą obecnością Ukrainek i Ukraińców w naszym kraju oraz przekazami medialnymi na ich temat.

Agnieszka Lichnerowicz (AL): In spring 2022, millions of Ukrainian refugees were running away from Russian aggression and violence towards Poland and Romania. Among them, a completely new type of migrant for both hosting societies: people with disabilities. As have been said thousands of times neither Poland nor Romania was prepared to receive such a high number of refugees, but civil societies and people responded immediately.NGOs and private citizens did not wait for governments to act. It will be a very shameful waste if what they have learned was forgotten and not used in case of next crisis and emergencies. That is why Polish-Romanian experience, lessons learned are the topic of this episode of the podcast, and that is why we have special guests. We have a pleasure to have special guests from Romania, Romanian academics, professor Bogdan Voicu.

Bogdan Voicu (BV): Hello. Nice to meet you

AL: And, Dr. Alexandra Deilu.

Alexandra Deilu (AD): Hi.

AL: And my name is Agnieszka Lichnerowicz and I will have the pleasure to moderate the discussion in the podcast. Maybe I shall introduce you in just couple of words, although I could much longer. Professor Voicu is a research professor with Romania Academia and he’s also a professor of sociology research methods and quantitative methods at major Romanian universities. And Dr. Deilu is a researcher at the Research Institute for Quality of Life at the Romanian Academy. First, maybe I could ask you, why should we focus, why you decided to focus on this Polish -Romanian experience?

AD: Apart from the funding opportunity, which was important.

AL: Maybe this is a great moment that I will underline, that the project was financed by Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange. The title is „The Capacity of Polish and Romanian Stakeholders to provide support to Ukrainian refugees with disabilities in the metropolitan areas of Warsaw and Bukarest”. And it is a project realized by Research Institute for Quality of Life and Civitas University. So again, why Polish? Except for that reason. Polish-Romanian Cooperation. Yeah.

AD: So what was interesting in comparing these two countries, in choosing them actually, was that they have some similarities, but at the same time some very important differences. And I’ll probably start with differences. First of all, they are different when it comes to the number of Ukrainian war refugees or displaced people who chose them as host countries. In Poland, the number of Ukrainian refugees was, and still is a lot higher than in Romania, almost five times higher,

BV: Something like that.

AD: About five times higher. So we have different scales. We have one country that receives less Ukrainians because it’s probably harder to reach for Ukrainians than Poland. And at the same time we don’t have a Ukrainian diaspora already in Romania. Whereas in Poland there are economic migrants from Ukraine who are here before the war. There are also differences when it comes to civil society and treatment of disability. The attitudes towards disability, and actually this is also one of the very important findings that we have, that things in Romania and in Poland are different when it comes to service providers dealing with people with disabilities. This sector is much more developed in Poland than in Romania, and we also have similarities between the two countries. As I said, probably the most important one is that both of these countries, as you also mentioned, had very little, very limited experience in receiving refugees prior to the Ukrainian war. Probably Poland had a bit more experience because you had refugees from Belarus. For example, in Romania, before the war in Ukraine, there were maybe less than 10,000 refugees, I think. So this was a big change for both of them. For both Poland and Romania. Another similarity resides in their past. Their past dominated by the Soviet era and the Soviet actors. So this to our mind made interesting mix.

BV: And I would add another similarity, which is not necessarily on the top of our agenda in the project, but it’s really relevant for the contemporary political developments that we experience here, both in Romania and in Poland. We have this friction in society between a more traditionalistic part, which are going towards the right wing extreme and the rest of society. And we both had elections in the past month with different outcomes. That are also shaped somehow by the incoming of these kind of refugees because these guys are on one term, Ukrainians, which means part of a country which includes provinces of former Poland, former Romania. Yeah. We’ve some historical turmoils in between and not a very clear understanding of the borders right now. On the other hand, they are disabled, which means a little bit outside of normality. And one of these people, one of these one of the disabled disabilities, one of the categories which is accused by the extreme right as disturbing nations. Somehow this migration flow is also very closely related to the phenomena which is undergoing in our societies.

AL: Before we go through the challenges that were faced by both Ukrainian refugees and hosting societies and the lessons learned, your toolkit you prepared based on your research. Can you say a little bit more about the method, how you research the NGOs?

BV: We have, two stages in our project because actually there are two projects, consecutive ones. One of them was to look to the, civic society and the public service providers, meaning the public administration ones, and look to how they deal with the case of this apparently invisible kind of migration because they didn’t expected it. The organizations who are dealing with migrants were not very clearly knowing what to do with the disabled and the ones which are looking to disable were not able to deal with migrants. So that was one of the stories we looked to service providers. Now, in our days, actually even today, we have an interview undergoing. We discuss with the disabled themself, to have a kind of triangulation of the perspectives from both the organizations and the beneficiaries. And we also have data, but from other projects that are complimentary about attitudes of the general population.

AL: So maybe it’s the spoiler, but do you believe that there’s a chance that both societies Polish and Romanian will learn from that experience?

BV: Yeah, sure. Yeah. Actually, actually this is one of the main outcomes of the project. We discovered that and many of our respondents told us literally that wow, if the war will start today, we would know what to do. This is a kind of experience that they learn a kind of thing that. And again spoiler of spoiler. One of the things that our society should not lose, we get some expertise now. We should use it not necessarily on our territories, but we should export it. This kind of expertise that we accumulated here in, Warsaw and Bucharest, we may use it in the aftermath of the world in Ukraine and in other theaters of war.

AD: Because providing services to disabled people is problematic, not only in the case of refugees in both Poland and especially in Romania. So being a refugee is an extra vulnerability, right? But being disabled is quite problematic because you have several issues that you have to face in order to access the proper services.

AL: Can you say a little bit more now about the group? Who are we talking about it? What kind of challenges, when we talk about Ukrainian disabled refugees?

AD: I think Bogdan wanted to add something.

BV: Yeah, maybe would go following up with the question. Normally in one society you have something like between 15 and 25% of operation who has a sort of disability. When we talk about disability, traditionally with the former communist stereotype that you have, we think mainly about not having a leg, not hearing enough, being blind and things like that. But it’s also about having a kind of chronic disease like cancer or I don’t know, some other diseases that I don’t come to my mind.

AD: Something that is non apparent, right? Yeah. When you look at a person, you cannot place that,

BV: Impeded you to act as a, let’s say, normal, regular person. Therefore, you have a lot of these kind of guys. In Ukraine they’re not defined as such. They are less. It’s on the flight mode. Yeah. This is we can leave it, we can leave it because, you’ll see I will take it from here. My phone just make the a small sign. It’s like this invisible disabled refugees, which came to your country that you don’t expect them to exist. And out of the blue, you find out that a fourth of the migration is made up of these persons because they come and they come with the caretakers.

AL: It’s fourth, you said the number is fourth. So it’s one fourth. Yeah.

BV: 25%. Quarter, quarter.

AL: Above the average for this society.

BV: Exactly. Exactly. And they come with the caretakers. Some of them are injured during the war, and they became with a sort of disability because of that. Some are not, some are autistic, ADHD or things like that, and you have no tool to deal with it. And this is another finding that we have, which is really important. We need to be prepared. In the beginning, in both Poland and Romania once they came to the border they have to fill in a form, but it was no indication if they have a disability or not. Therefore, they’re put in some reception centers which are not adapted to their needs and… adapted to the needs- you usually know about toilets and stairs and ramps and things like that, but it’s not only that if you have an autistic one, you cannot put it in the dormitory with other people. Because it’ll have a, it’ll be a problem. And if you have an intersection, far intersection with ethnicity, let’s say Roma ethnicity, it’s even worse.

AD: So probably one of the most important findings is that we need to collect data. We need to have this exercise to gather as much information as we can about the people that we are trying to provide services to. So we have to know what persons need in order to be able to address their needs properly.

AL: So that’s what professor said. We have to see them first. To understand that…

BV: You have to be proactive, you have to think in advance about what will happen when they come. Because in both countries the war came out of the blue. We have a saying in Romania „we are taken by surprise by the winter time”. But winter time comes all the time. You have to prevent winter time. You have to know that will gonna snow if it’s in winter, and you have to have all the tools in order to take the snow out of the streets. It’s the same with the refugees: we learned now, and this is a valuable knowledge that when refugees do come, we have specific trauma to address, specific needs, communication needs, language things, and things related to disability that we need to have in mind from the very, very beginning.

AL: Can you give more examples for us to understand better? What were the challenges? You mentioned at first that without the knowledge about the disabilities that the person may have, we can place him in a room in a place where it will be difficult for him to survive. How is it with communication, like with people with blindness, for example, or deaf people? The languages, how does it work? Is it possible to be prepared to know all the languages?

AD: First of all, it’s something to be addressed. Prior to this, it’s the fact that communication was pretty hard because there were not enough translators. So communication with people who are not blind or deaf was quite hard, especially given the fact that the situations…

AL: I guess in Romania it was more difficult because in Poland the languages are close.

AD: Actually we don’t have any documented cases of people with blindness or deafness.

BV: Yeah we do have some in the interviews because the sign languages is not the same. You have a sign languages in Ukrainian, sign languages in Polish, yeah. Another one in Russian, because this is the problem. So communication always difficult with the blind people from this point of view. It was also difficult, as you said for regular people, not only for the one with blindness. We used in Romania, we used the Moldavians because many of them also now Russian and Ukrainians also communicate in Russian. So it was the, this kind of case. But the biggest challenge I think in Romania, not necessarily in Poland, but in Romania, it’s very clear, was to go to the doctor. Because you need a doctor that speaks Russian. We didn’t learn Russian in school. The generation of my parents had for a very short while Russian in school. But after that we had French, English, German. And I’m born way before the communist fall down. So we couldn’t find doctor to, to speak their language. And you need the translator at all time. And the translator should be quite good in medical stuff. Both in Russian or Ukrainian, and in Romanian or English: that was not easy. And then you don’t have a clear equivalence between the disability certificates in the EU, including Romania and Poland, and Ukraine, which are different and not recognized. And in order to get your benefits as disabled, you need to certificate, and to get a certificate, you need to go to a doctor, and it’s an entire catastrophe coming from communication to transportation. To fitting the program and the hours of the voluntary people that you use of the member of the NGOs, which also had the difficulty of upscaling. We have organization come starting with four employees in the beginning of the war and ending up with 120. Which mean, which means a lot of pressure on the organizational culture and in selection of the new recruits.

AD: So it was a great deal of organization necessary in order for people to actually access the services coordination between different actors, different levels of service providers or medical staff, social workers, or maybe personal assistance or translators and so on and so forth. So this was probably an important aspect, getting people to work together in order to make sure that potential beneficiaries actually become beneficiaries, actually get access to the services that they need.

BV: And then you have a question of distribution of resources. NGOs are more flexible so they can adapt to what comes and to do things, but most of the resources are in the public space. And there you have a lot of regulation, norms and methodologies that you have to respect and, you cannot deal case by case with everyone. This is why we have civil society, which is substituting the public provision. But in the beginning of the war, it was a timer because nobody had the tools. The resources are here and there. There are many voluntary coming and trying to do things, volunteers, but it was kind of a mess, not nothing organized overlapping services that are missing completely. And it took a very long while up to settling down and then, when everything was somehow clear the refugee flow started to decrease. So there is not so much need. And the enthusiasm of both societies decreased and the resources allocated decreased, and organizations started to become smaller again. That’s not very easy to palate.

AL: That’s what I wanted to ask you about. The long term prospects. People with disabilities say groups that very often will not be able to sustain themselves by their work. And that’s what is the goal often to make people self sustainable. Here in Poland, we are very proud that so many of the refugees found jobs and they actually been, we benefit as a country, as a budget more from them being here than they take from the budget. But how is it in Romania, especially as far as long-term prospects of the refugees with disabilities are concerned both do they have still care or they were forgotten? Are there programs to help them in a longer term? And how is it with official and bureaucratic procedures also for them being legally in Romania?

AD: People, Ukrainian refugees with certified disabilities do not have to work in order to get benefits from the state, benefits from being in, in Romania. At the same time in Romania, the discussion and the studies. Let’s say the scientific discourse or academic discourse about people with disabilities actually stresses integration, as you said integration in the workplace, in the labor market, and the ability of people to sustain themselves. This is an important aspect. At the same time, to my knowledge at least, there are not any programs targeting refugees with disabilities and their integration in Romania. I don’t think that they are.

BV: No, they’re not. And as a matter of fact, while regular Ukrainian migrants started to integrate in the local economy, you can see them because, for instance, in the Bukcharest region, the unemployment is almost zero. So it’s a chronic deficit of labor force. So they are more than welcome from this point of view, and they actually started to learn Romanian, and they manage quite well. The biggest problem is with the children. Polish and Ukrainian are somehow close, but Ukrainian and Romanian are far from being closed, and the Roman education system has very little interest in helping even Romanians, not to mention Ukrainians. So it’s quite difficult for them and they’re still attending classes online from Ukraine. Both children with disabilities and regular children, but in particular the ones with disability because it’s even more difficult for them to be actually in a school in Romania. And for this kind of persons I don’t see much integration for the moment. And that’s a little bit challenging.

AL: There is also one more point in your report from the research and in a toolkit that is underlined is this emotional burnout of the NGOs, activists. Why is it so much underlined by you? Was it more challenging for people that were supporting the refugees when they had to support refugees with disabilities. Why? Why do they underline it so much?

AD: For example, in the case of Romania, when it comes to public service providers, the adminis, local administration, let’s say people, social workers, let’s say were assigned to take care to provide services to refugees, not refugees with disabilities, just refugees. And this was something new to them, totally new because they were not equipped to deal with refugees because they didn’t do that prior to the war and they found themselves in a new situation having to deal with different traumas that they were used to. So this actually caused a lot of burnout on one hand. On the other hand, probably a less effective work plan, let’s say, and these issues had to be overcome. Burnout in general was probably due to the fact that Poland and Romania had little experience with refugees, as I said. So people were not actually accustomed to working in such a high speed, let’s say.

BV: And it was also a kind of urge to provide more and more services. Because you learn that you can do it. And then they started to have less resources and they still wanted to provide everything. Yeah. And they put the pressure on them trying to be there, help them. And then you know that every single therapist need a therapist. It’s the same if this kind of social workers and out of a many of them are not trained as social workers, as helpers, and they need support. Some of the organization both in Poland and Romania, they started to provide some support, but others not. And from this point of view it was very tough. And the burnout happened.

AL: I guess it’s also due to the fact that both in Poland and Romania, civil society says we underlined, took so much of the burden on themselves, not the government and institutions. So usually people had to work the regular jobs plus this additional one. That is, I would ask you the toolkit for service provision supporting war refugees with disabilities you prepared all the researchers that took part in this research. Is it more for NGO or for the governments and official state institutions or?

BV: As a matter of fact, it addressed the needs for both type of service providers and also for decision makers, because if you’re a decision maker you need to do it before things happen. From this point of view it’s really useful for everyone including volunteers. If you have volunteer going, it doesn’t matter in which kind of organization they may read it and use it and is not targeted on Poland and Romania. It’s somehow universal. The same kind of phenomena and processes you find all over the place.

AL: So also you think this experience that we have had here is, would be useful in Germany or Britain.

AD: Yeah. Because there are some general ideas here. Yeah.

BV: But to a less extent in Germany and Britain, which have more experience than you have. Sure. But it may be useful in Azerbaijan, Ghana, in Nigeria.

AD: Let’s say countries with a similar level of experience.

BV: In countries which are bordering now Iran and Israel, in Turkey. Why not in Malta? Because it’s on the border of European Union. And I think that it’s not a very good economic moment, but our government may think about programs of international development because sending this kind of expertise abroad it’s one step in order to put our businesses there.

AL: Yeah. So can you give just a couple of examples of the know-how one can find in the toolkit that is for everybody for free on the website of the project or anybody can download it, but what would you underline from the practices you…

AD: The importance of coordinated communication? Both vertical and horizontal. Horizontal as in actors or stakeholders in different domains, disability and refugees or immigrants. It’s also important to be able to import knowledge from transnational actors as in NGOs or service providers in other countries like Germany and Britain, as you said, who might have a more structured knowledge in how to deal with different situations. It’s also important to offer services that allow people with disabilities to be self-reliant as much as possible. In a rough translation to help them at the beginning to teach them or show them how the system works, the social system in the host countries, but then to try to gradually invest energy into making them be able to actually fend for themselves.

BV: And also it’s not only at the level of this very nice and clear principles that you have to follow, but also to some banal things like what to do when we don’t have the toilets toilet leads. Maybe toilet chair needs a lead. You might be creative. And we have examples with our interlocutors saying what they did and how they bring it from home or find somebody else to bring it and how to make a ramp or things like that. We have a lot of tedious examples in the toolkit, but also the principles that Alexandra was talking about, which are really strong and the ones that you should start following.

AL: Question to you; if we should add anything else that I haven’t asked.

BV: Yes. First of all, I wish we have no refugees and no war. Second of that, if we have it, let’s do it properly.

AD: I mean the reception, not the war. There was actually an interesting idea that I found in an article some while back, that it’s somehow not right or not correct to say that there is a refugee crisis. It’s a crisis in the provision of services maybe, but refugees themselves are not the problem and should not be treated as a problem.

BV: And also at the, on more general level, we said it in the report that we have lessons here, that we learned, that we can use in the daily life. Not dealing with refugees, but in service providing in the communication side, as you said, the cross-domain. And one is really important for every kind of intervention and helping beneficiaries, which are in need.

AL: Can you give an example of that?

BV: For instance, if you have someone which is both old, elderly and disabled, you need specific intervention for disabled that’s for elderly, which means that the organization that have expertise in these two fields should learn from the others and cooperate when it comes to provide the service to this kind of beneficiary.

But you may also have children, young people. I mean, age is not necessarily an issue but you have the intersection of two needs. Unique communication with the other who are specialized in the other need.

AL: And I would underline what you have said at the very beginning that it’s a quarter, 25%, more or less, of all the refugees, I think that we are still not aware of, or deeply aware of that fact. Thank you very much for the conversation and for the research. Professor Bogdan Voicu and Dr. Alexandra Dailu were both the guests of the podcast today, they are the co-authors of the research on the Ukrainian refugees with disabilities that arrived to Poland and Romania, the research that was based on cooperation between Civitas University and Research Institute for Quality of Life in Romanian Academy. And part of this research, as we mentioned, is this toolkit for everybody to be downloaded on the website of the project. Thank you so much.

BV: We thank you. It was a pleasure.

outro:

Projekt został dofinansowany ze środków budżetu państwa przyznanych przez Ministra Edukacji i Nauki w ramach programu Społeczna Odpowiedzialność Nauki II. Popularyzacja nauki. Dziękujemy za uwagę i jednocześnie zachęcamy do subskrybowania naszego podcastu Civitas On Air, który jest dostępny w popularnych serwisach streamingowych. Uniwersytet Civitas znajduje się także na Facebooku Instagramie i portalu LinkedIn. Zachęcamy do śledzenia naszych profili.

Civitas on Air to podcasty o szeroko pojętej tematyce społecznej przygotowywane przez badaczy i badaczki z Collegium Civitas we współpracy ze studenckim Radiem PałaCC. Wierzymy, że badania naukowe mogą być ciekawe nie tylko dla naukowców, a popularyzacja wiedzy jest równie ważna, jak jej zdobywanie.

Civitas on Air to podcasty o szeroko pojętej tematyce społecznej przygotowywane przez badaczy i badaczki z Collegium Civitas we współpracy ze studenckim Radiem PałaCC. Wierzymy, że badania naukowe mogą być ciekawe nie tylko dla naukowców, a popularyzacja wiedzy jest równie ważna, jak jej zdobywanie.